the effort of creation

what is the point? anything you can do, machine can do better? musings on the value of art, genAI, and the intersection of technology and art

warning: some spoilers for the movie/manga Look Back, which I highly recommend

“Fujino, why do you draw?”

There is something within me that yearns to create. I see an inspiring project, whether artistic or technical, and I crave the ability to produce something which strikes in others the same awe that it has struck in me. But to create something substantial, to fully realize the lofty ambitions in my mind, is hard work.

I might attempt, only to feel discouraged upon seeing that what I am capable of with my current skill is so distant from what I desire. Of course, I know that I am not stagnant, I can grow. But there will always be someone who has already put out something at a level I may never reach, someone who is and will always be better. So why try?

This is a theme explored in Look Back, a manga by Tatsuki Fujimoto that was adapted into a film.

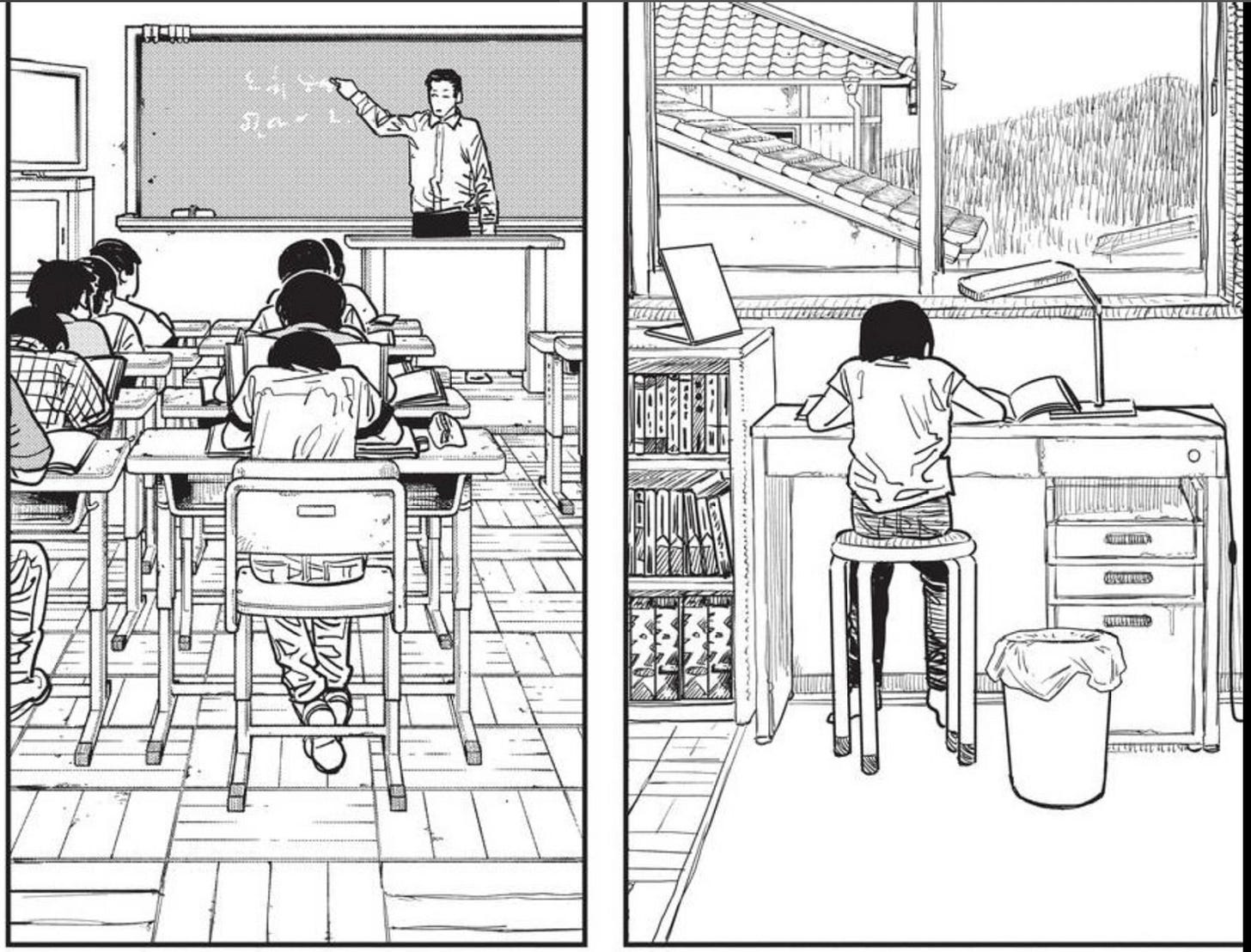

Fujino is a fifth grade artist that draws comedic manga strips for her school’s weekly paper. She relishes the praise that her classmates shower her with every time the new edition is passed out. She has an ego.

However, her pride is shattered when another student, one year younger than her at that, starts publishing manga strips with obviously more advanced drawing skill.

Fujino has never met her competition before; this newcomer, Kyomoto, is an agoraphobic truant. But with her core identity threatened, Fujino is imbued with a fiery desire to improve her art, and devotes the next few years to practicing, at the cost of her academic and social health.

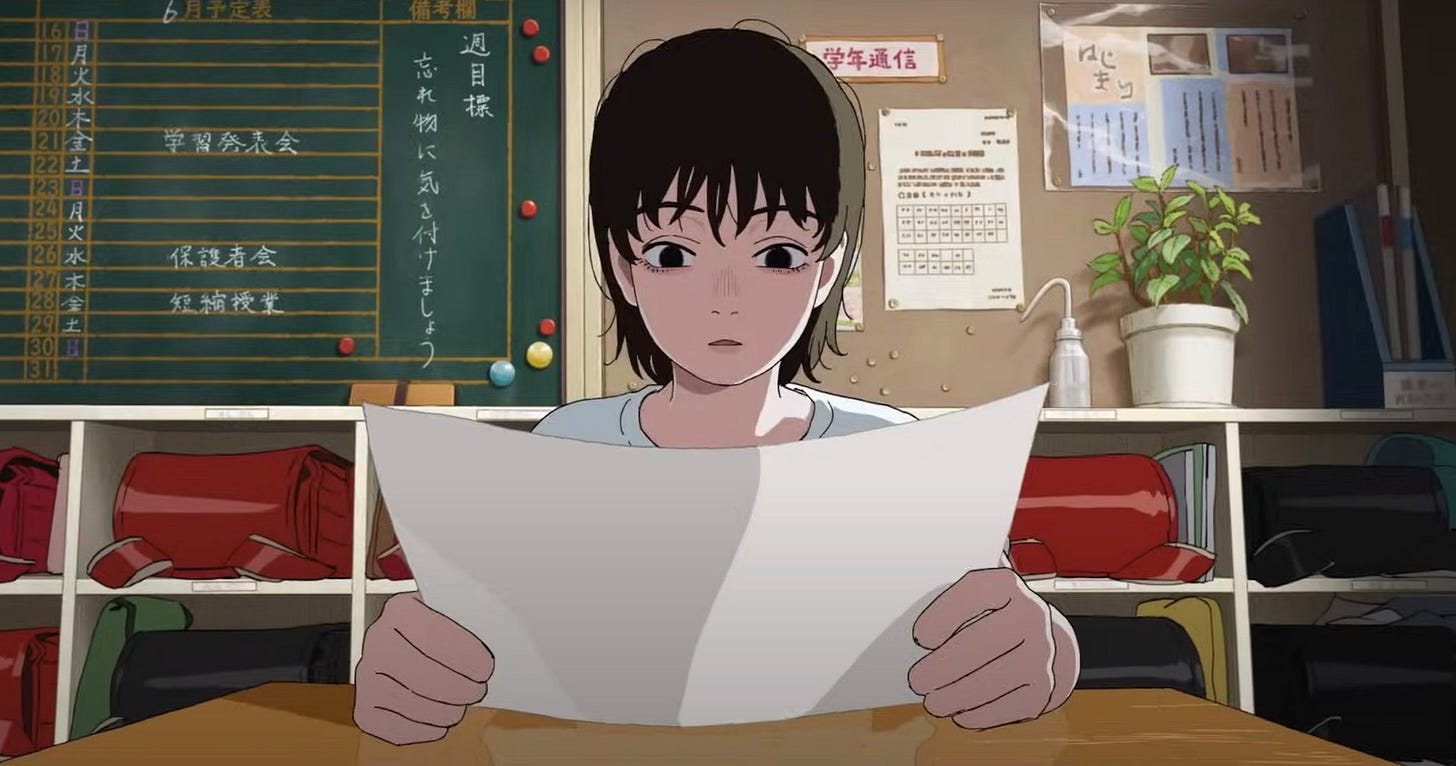

To conclude this training arc comes a simple, powerful scene:

Many seasons have passed. The weekly paper is passed out. Fujino looks down at her and Kyomoto’s manga strips printed side by side. It is clear, to both her and us, that after all of Fujino’s single-minded dedication and effort, Kyomoto’s drawings are still unarguably superior.

Fujino says to herself, quietly, “I quit.”

She goes home and puts away her art supplies, discards piles upon piles of sketchbooks without hesitation.

I believe many artists, including myself, can relate to Fujino to some extent. It’s discouraging to put in so much work, only to find that there’s still this insurmountable distance between where you are and where you want to be, no matter how far you may have come from the start.

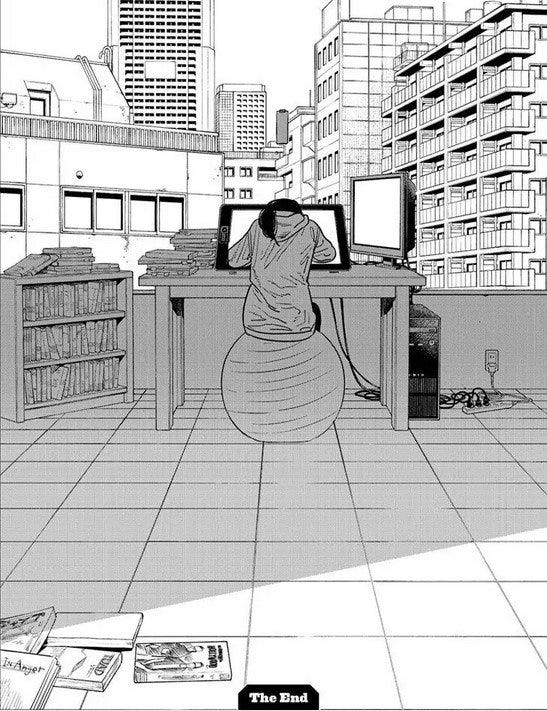

But this isn’t the end of the story. Fujino will discover that Kyomoto has actually greatly admired her work all these years, and they will team up to create competition-winning manga. Fujino draws again. Even after senseless tragedy occurs, Fujino draws.

Why do you draw, Fujino?

“The seats are dark, the theater is empty, so why do you keep dancing?”

This is a question perhaps more relevant now than ever, with the surge of easily accessible, generative AI tools actively devaluing the work of human artists.

I don’t want to debate whether AI art is real art or not, yet. I just want to describe what I see, from the perspective of a hobbyist who grew up entrenched in online art communities and spent a period of time living like Fujino, desperately working to improve her artistic abilities:

I see aspiring artists grow jaded and lose motivation to improve upon seeing how easily AI can generate art. I see freelance artists saying that their commission requests have significantly diminished after the onset of AI hype. I see social media accounts trying to pass off generated work as non-AI. On posts of hand-drawn art, I see accusatory comments: “This looks like AI.”

To prove that they drew the work by hand, digital artists have resorted to posting speed paints. A few months ago though, I saw someone share that AI could now generate such speed paints. As it seems to appear these days, anything you can do, machine can do too. Anything you can do, machine can do better.

On posts criticizing non-artists that use generative artwork to bypass the need to hire real artists, I see dismissive comments like: “Who cares? Not everyone can afford to pay an artist or designer.”

One common counter to that is: art is and has always been a luxury. Is that to say that not everyone deserves access to nice art? That’s not right, and yet neither is the fact that these models are often trained on non-ethical datasets scraped from the laborious work of non-consenting artists. But the ethicality of generating art is not the main subject I want to discuss, rather, the value that remains still in being someone who dedicates great time and labor into creating art.

Efficiency is king. Capitalism encourages cutting costs. When you can get something good enough with a sentence and a click, why pay for soul?

Is there any longer a point to the painstaking labor of practicing the foundations, doing anatomical studies and studying color theory, putting in years of effort just to be able to create works that many people will dismiss in favor of a quickly generated image?

“It’s not that deep” is a common rebuttal. I hate that one, because isn’t it? Everything is deep. The apathy is depressing. Everything means something, everything comes from something and leads to something else.

On one end of the spectrum, I see condescending comments proclaiming that they hope all artists will eventually be replaced by AI. While others may not hold such an extreme view, I’ve observed that a large portion of people using AI art tend to be non-artists that do not fully respect artists. I find it sad that there are people who see such little value in creative endeavors. It has immense value. That is what I believe, and this is my attempt to articulate why.

The director of the film, Kiyotaka Oshiyama, addresses the importance of humanness:

"I deliberately tried to leave lines that looked human. Lines contain the artist's feelings, their will to paint something. If you trace them and make them look mechanical, the information in the lines is lost. I tried to show the lines directly on the screen.

[...] Because it's becoming easier to create beautiful images using AI, I think these lines drawn by humans still have their place. Even if AI were to imitate humans and reproduce the rough sketches, it would just be a design. It would be a fake. The lines have meaning because they were drawn by humans. This may be the last time we'll be able to do this, but there's value in that. It's also connected to the praise of creators." (source)

I think this film came out at an important time. Within the current AI bubble, in which everyone is so focused on optimizing away human inefficiencies, the film celebrates the journey and raw labor that artists undergo; the effort of creation.

I have always liked to see process. The drafts, the ideation, the scrapped sketches. I want to know what the maker intended! The intention of every element!

I do not believe there can be such intention with AI. AI does not really understand what it makes, the way we understand what we make. It makes what is probable based on what it has seen before. It doesn’t imagine, it computes.

How important is intention in art? This could spiral into discussing modern or contemporary art, Yves Klein’s Blue Monochrome, the “I could make this too”.

Ted Chiang, the sci-fi author who famously wrote the short story that the movie Arrival was based on, published a piece in The New Yorker titled “Why A.I. Isn’t Going to Make Art.” (source)

In the essay, Chiang acknowledges that “art is notoriously hard to define,” but provides a generalization: “art is something that results from making a lot of choices.”

Chiang argues that the non-deterministic behavior of generative AI is an inherent limitation that bars it from creating real art. He also addresses the common argument that generative AI parallels the advent of photography:

“When photography was first developed, I suspect it didn’t seem like an artistic medium because it wasn’t apparent that there were a lot of choices to be made […] But over time people realized that there were a vast number of things you could do with cameras, and the artistry lies in the many choices that a photographer makes […]

Is there a similar opportunity to make a vast number of choices using a text-to-image generator? I think the answer is no. An artist—whether working digitally or with paint—implicitly makes far more decisions during the process of making a painting than would fit into a text prompt of a few hundred words.”

Yes, if somebody were to create something through several sessions of prompt engineering to craft an image with intention, with as much fine-grained control as possible, Chiang concedes that that user could “deserve” to be called an artist. But that’s not the main goal of these tools, and that’s certainly not how they’re most commonly utilized; “The company wants to offer a product that generates images with little effort.” The companies can claim that AI promotes creativity, maybe democratizes art-making, but Chiang says:

“Art requires making choices at every scale; the countless small-scale choices made during implementation are just as important to the final product as the few large-scale choices made during the conception.

[…] Believing that inspiration outweighs everything else is, I suspect, a sign that someone is unfamiliar with the medium.

[…] Generative A.I. appeals to people who think they can express themselves in a medium without actually working in that medium. But the creators of traditional novels, paintings, and films are drawn to those art forms because they see the unique expressive potential that each medium affords. It is their eagerness to take full advantage of those potentialities that makes their work satisfying, whether as entertainment or as art.”

Chiang puts it well. To answer the question of what art is, one can say that art is about choices.

But what about why we make art, or what purpose art serves?

Even without bringing AI into the conversation, the intellectual pursuit of the arts and humanities is still, to many, considered inferior to that of science and engineering.

In “Art Is How We Justify Our Existence,” an essay in The New York Times, writer David Zwirner says:

“Great art is, by definition, complex, and it expects work from us when we engage with it.

[…] I would contend that art and culture are the most important vehicles by which we come to understand one another. They make us curious about that which' is different or unfamiliar, and ultimately allow us to accept it, even embrace it.”

I want to pivot slightly to say that despite the prior discourse, technology is not antithetical to art. AI actually plays a very interesting role in new media art, and for those unfamiliar with the genre, I want to introduce it with some pieces I admire, for personal indulgence. (a picture says a thousand words. but does it when it’s made with ten?)

The Wind from Nowhere, by Haein Kang, is a data-driven sound installation:

“Based on the wind data blowing somewhere in the world, this work is passively reminiscent of the wind by changing the way the paper is shaken. When the machine synthetically gets consciousness, can this phenomenon be regarded as the beauty of the wind for them?” (source)

Autophotosynthetic Plants, by Gilberto Esparza, is a symbiotic system that reimagines sewage as a source of energy:

“The modules create a hydraulic network that administers bio-filtered water to the central container, creating an optimal environment where producer species and consumer species from different trophic levels (protozoans, crustaceans, microalgae, and aquatic plants) can achieve homeostatic equilibrium.

The electricity produced by the bacteria is released as intervals of luminous energy, enabling photosynthesis by the plants that inhabit the central container, which thereby completes their metabolic processes.” (source)

I actually showed the above piece to a friend, who was impressed, but asked, “How is this art?”

I also showed it to my dad, who asked, “Isn’t art meant to be beautiful?”

There is a common belief that art should look a certain way. This doesn’t look like an art piece, so how is it art? Conversely, if it looks like art, is it art?

I like Chiang’s definition of art. Some of my own are that:

It is a demonstration of human creativity

It communicates a way of seeing the world

It is the materialization of a perspective built from deeply personal interests and experiences

It is a human endeavor of self-expression based on a uniquely personal lived experience

It is about the process of creation

I hope this essay provides enough evidence that art matters, and that most generative works today are not art.

The main questions I had hoped to answer for myself were:

Why draw?

Why create?

Why did I write this?

(I knew the answer from the start)

I see an inspiring project, whether artistic or technical, and I crave the ability to produce something which strikes in others the same awe that it has struck in me.